|

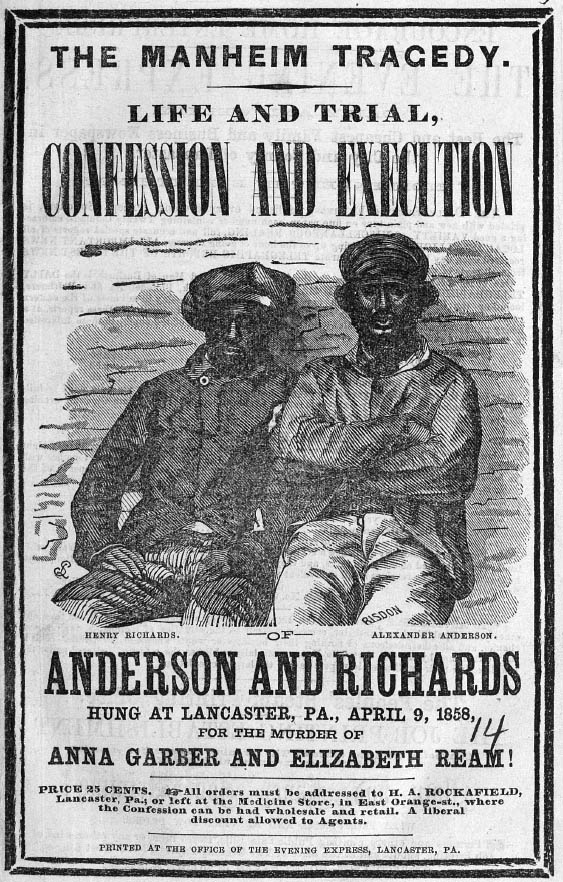

| Richards & Anderson |

On a sunny December morning in 1857, Mrs. Anna Garber and Mrs. Elizabeth Ream were raped and murdered in Mrs. Garber’s home in Manheim, Pennsylvania. Evidence overwhelmingly pointed to Alexander Anderson and Henry Richards, two African American workmen seen in the neighborhood. Though there was little doubt as to who committed the murders, a question still remained: would they be tried by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania or would the case would be handled by "Judge Lynch."

Date: December 15, 1857

Location: Manheim, Pennsylvania

Victim: Mrs. Anna Garber and Mrs. Elizabeth Ream

Cause of Death: Blows to the head, Slashing

Accused: Alexander Anderson and Henry Richards

Synopsis:

Anna and Conrad Garber had raised ten children in their farmhouse in Manheim Township, “one of the most beautiful and fertile sections of the country.” On December 15, 1857 the peace of that township would be shattered by a tragedy more outrageous than any seen before in Lancaster County.

Conrad had gone to work, leaving his wife in the kitchen making butter. Their neighbor, Mrs. Elizabeth Ream stopped by that morning to visit with Anna Garber as she worked. The women were related by marriage, Mrs. Garber’s daughter Mary Ann had married Mrs. Ream’s son.

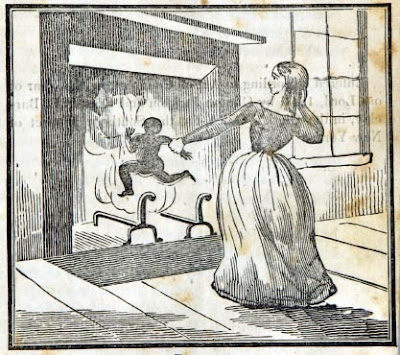

Around 1:00 Mary Ann Ream stopped by as well, “to keep the old folks company.” When she opened the door to her mother’s house, Mary Ann knew something was wrong. The furniture was in disarray and there were bloodstains on the floor, but nothing could have prepared her for the horror she found in the back room. Her mother and her mother-in-law both lay dead on the floor, their skulls cracked and their throats slashed from ear to ear, each body lying “in an indelicate position.” Money and some other articles had been stolen, and one of the assailants had left behind a pair of shoes. As soon as she recovered from the shock, Mary Ann fled the house and alarmed the neighbors.

Suspicion immediately fell on two African American men (one was described “a mullato speaking the German language”) who had been looking for work in the neighborhood that morning. Around 11:00 they stopped at the house of Isaak Kaufman, who lived opposite the Garbers, and said they were sweeps and wished to clean his chimneys. When Kaufman said he had no work for them they asked him for food and he gave them some bread. Kaufman saw them walk to the Garbers’s house and assumed they found work there because he saw them enter but did not see them leave.

The killers had not been hard to capture; they had been seen heading down Litiz Pike towards Lancaster and were arrested in that town in time for the story to be printed in the evening paper. They were taken to the Mayor’s office where they identified themselves as Alexander Anderson and Henry Richards. Anderson had $90 in gold and silver under his shirt in a salt sack tied in a silk handkerchief. Richards had three dollars wrapped up in a piece of German newspaper, similar to one found in the chest where the money was taken. He was also wearing Mrs. Garber’s shoes - a pair of boots she would wear to market. A handkerchief with black bars in Anderson’s possession was a perfect match to one worn by Mr. Garber. They had been cut from one piece of cloth that Mrs. Garber hemmed into two handkerchiefs.

News of the murders and arrests travelled quickly, spreading outrage throughout Lancaster County. The shock of the brutal act and the anger directed against the killers is expressed in this self-censored passage from the murder pamphlet The Manheim Tragedy.

Their double-murder was the work of a triple motive—they demanded blood—gold—and————. The heart sickens—thought recoils within the dungeon of the mind—imagination palls—the pen involuntarily stops, at the contemplation of such a compound deed of fiendish brutality. While it was enacting, angels wept and averted their earth-reaching eyes, unused to look down upon such human depravity; and devils trembled at the contemplation of the consequence of their own hellish conception and instigations.The fact that the two killers were black fanned the flames of outrage, and as Anderson and Richards were being questioned, a mob formed outside the mayor’s office. Shouts of “Lynch the damned niggers!” could be heard emanating from the growing crowd. It looked as though the crowd was ready to act on that suggestion when the officers brought them down from the mayor’s office, but the prisoners made it safely to the jail.

The funeral of Mrs. Garber and Mrs. Ream took place the following Thursday morning. Sermons were preached by three ministers, one Lutheran, one German Reformed, and one German Baptist but rather than subduing thoughts of violence, their solemn words only enflamed the crowd all the more. A mob gathered again around the jail, forcefully testing the strength of the walls. Some expressed a lack of faith in the courts, fearing the killers might be set free by some legal technicality. There was talk of saving the state the cost of a trial by taking the men into the woods and burning them alive.

The jail was surrounded again on Saturday, December 19, the date of the preliminary hearing. Fearing mob violence, the aldermen decided to hold the trial in storeroom of the jailhouse rather than at the courthouse. After the prisoners were identified by witnesses, and evidence of their guilt presented to the court, Anderson and Richards were indicted for the murders of Anna Garber and Elizabeth Ream and their trial was set for the third Monday of January.

By the opening day of their trial, fervor for lynching Anderson and Richards had died down, but interest in the case had not. Before the trial commenced, every seat in the courtroom was occupied and the hallways outside were filled to capacity. The sheriff ordered that no one else could enter unless someone inside left, but crowds rushed the doors anyway, pushing their way inside. Finally the sheriff locked all of the doors, allowing no one in or out until the trial ended for the day.

Anderson and Richards were tried separately and Anderson’s case was taken first. Though he pleaded not guilty the testimony and evidence against him was overwhelming. Anderson’s court appointed attorney offered no real defense, but cited cases where relying on circumstantial evidence led to the conviction of the wrong man. He hoped that the growing sentiment in Pennsylvania against the death penalty would persuade the jury to convict his client of a lesser charge. The jurymen were not convinced and took only a few minutes of deliberation to convict Alexander Anderson of first degree murder.

Henry Richards’s trial the following day was even quicker. His attorney responded to the same evidence by arguing that Richards was weak of mind and easily led. He had not participated in the murders, just agreed to stand by his partner and not give him away. Richards was also found guilty of first degree murder.

Verdicts: Guilty of first degree murder

Aftermath:

While awaiting execution, Alexander Anderson was persuaded by some clergymen to make a full confession. It would be printed and sold to provide money for his wife and children. Anderson wrote it himself but the confession was edited by the clergymen. Though they claimed that they only corrected the spelling, the clergymen probably adjusted the tone as well, making it was somewhat moralistic, especially regarding alcohol. Anderson wrote that he began drinking whiskey at age six and began stealing soon after.

Anderson confessed that on the day of the murder he and Richards had gone out intending to rob a house. Instead of his chimney scraper, he was carrying a hatchet in his belt to open trunks. He and Richards got very drunk before heading out. They went to the Garber’s house and asked about work and left when Mrs. Garber said she had none. Then they decided to go back and ask her for “a levy” to buy more whiskey. The violence started when Mrs. Garber refused to give them money. The two women put up a terrible struggle but were eventually subdued by blows to the head. Then, in Anderson’s words:

![]() On Friday, April 9, 1858, Anderson and Richards were hanged in the yard of Lancaster jail. More than two thousand people applied to witness the execution, but the Sheriff stuck to the terms of the law. The only official witnesses were the twenty-four jurymen who convicted them, the sheriff, two deputies, two clergymen and state senator Cobb – a proponent of the death penalty who attended all Pennsylvania hangings.

On Friday, April 9, 1858, Anderson and Richards were hanged in the yard of Lancaster jail. More than two thousand people applied to witness the execution, but the Sheriff stuck to the terms of the law. The only official witnesses were the twenty-four jurymen who convicted them, the sheriff, two deputies, two clergymen and state senator Cobb – a proponent of the death penalty who attended all Pennsylvania hangings.

Outside the prison walls, the public found other ways to witness the execution. People in surrounding houses could see inside the prison yard from their roofs. One entrepreneur erected a scaffolding on a hill outside the prison and charged a dollar a seat. Those without a view stood outside the prison walls waiting to cheer when the execution was confirmed.

At twenty-five minutes before twelve the trap was sprung and within five minutes both men were dead. The bodies of Alexander Anderson and Henry Richards were interred in the burying ground of the Lancaster Poor House.

Newspapers:

"Execution of Murderers." Springfield Republican 10 Apr 1858: 5.

"The Double Murder in Lancaster County." Sum 19 Dec 1857: 1.

"The Manheim Lancaster County, Tragedy." Public Ledger 27 Jan 1857: 1.

Anderson and Richards were tried separately and Anderson’s case was taken first. Though he pleaded not guilty the testimony and evidence against him was overwhelming. Anderson’s court appointed attorney offered no real defense, but cited cases where relying on circumstantial evidence led to the conviction of the wrong man. He hoped that the growing sentiment in Pennsylvania against the death penalty would persuade the jury to convict his client of a lesser charge. The jurymen were not convinced and took only a few minutes of deliberation to convict Alexander Anderson of first degree murder.

Henry Richards’s trial the following day was even quicker. His attorney responded to the same evidence by arguing that Richards was weak of mind and easily led. He had not participated in the murders, just agreed to stand by his partner and not give him away. Richards was also found guilty of first degree murder.

Verdicts: Guilty of first degree murder

Aftermath:

While awaiting execution, Alexander Anderson was persuaded by some clergymen to make a full confession. It would be printed and sold to provide money for his wife and children. Anderson wrote it himself but the confession was edited by the clergymen. Though they claimed that they only corrected the spelling, the clergymen probably adjusted the tone as well, making it was somewhat moralistic, especially regarding alcohol. Anderson wrote that he began drinking whiskey at age six and began stealing soon after.

Anderson confessed that on the day of the murder he and Richards had gone out intending to rob a house. Instead of his chimney scraper, he was carrying a hatchet in his belt to open trunks. He and Richards got very drunk before heading out. They went to the Garber’s house and asked about work and left when Mrs. Garber said she had none. Then they decided to go back and ask her for “a levy” to buy more whiskey. The violence started when Mrs. Garber refused to give them money. The two women put up a terrible struggle but were eventually subdued by blows to the head. Then, in Anderson’s words:

“We then had to do with both of the women, before they were dead. Richards had to do with Mrs. Ream and myself with Mrs. Garber.”Then they ransacked the house. The women were still groaning when they prepared to leave, so they cut their throats and killed them.

“Oh, I pray God that all who read this Life and Confession will give up drinking whisky,” Anderson added, “because now you see the fruits of whisky! If I hadn’t followed the practice of drinking whisky I would never have been in prison—I would not now be on my way to the gallows!”Henry Richards seemed indifferent to his plight and laughed at anyone who suggested he confess. He maintained his innocence with a series of conflicting stories putting all the blame on Anderson. But as his execution day approached Richards finally confessed as well, revealing details of the crime that corroborated Anderson’s confession.

On Friday, April 9, 1858, Anderson and Richards were hanged in the yard of Lancaster jail. More than two thousand people applied to witness the execution, but the Sheriff stuck to the terms of the law. The only official witnesses were the twenty-four jurymen who convicted them, the sheriff, two deputies, two clergymen and state senator Cobb – a proponent of the death penalty who attended all Pennsylvania hangings.

On Friday, April 9, 1858, Anderson and Richards were hanged in the yard of Lancaster jail. More than two thousand people applied to witness the execution, but the Sheriff stuck to the terms of the law. The only official witnesses were the twenty-four jurymen who convicted them, the sheriff, two deputies, two clergymen and state senator Cobb – a proponent of the death penalty who attended all Pennsylvania hangings. Outside the prison walls, the public found other ways to witness the execution. People in surrounding houses could see inside the prison yard from their roofs. One entrepreneur erected a scaffolding on a hill outside the prison and charged a dollar a seat. Those without a view stood outside the prison walls waiting to cheer when the execution was confirmed.

At twenty-five minutes before twelve the trap was sprung and within five minutes both men were dead. The bodies of Alexander Anderson and Henry Richards were interred in the burying ground of the Lancaster Poor House.

Sources:

Books:

Rockafield, H. A.. The Manheim tragedy . Lancaster: Printed at the Evening Express Office, 1858

(Courtesy of Readex.)

Slaughter, Thomas P.. Bloody Dawn. Washington: Oxford University Press, 1991.Newspapers:

"Execution of Murderers." Springfield Republican 10 Apr 1858: 5.

"The Double Murder in Lancaster County." Sum 19 Dec 1857: 1.

"The Manheim Lancaster County, Tragedy." Public Ledger 27 Jan 1857: 1.

,. Philadelphia: Joseph Jackson, 1918.

,. Philadelphia: Joseph Jackson, 1918.